Radio World

Author (when available): Nick Langan

Nick’s Signal Spot is a new feature in which Nick Langan explores RF signals, propagation, new equipment or related endeavors.

Growing up in the 1990s, I surely would have appreciated the DSP-generated selectivity of today’s car radio tuners and portables.

On the FM band, with a Walkman-type receiver, hearing a weaker signal 2 MHz away from a stronger one was always a challenge.

In technical terms, when a signal is 6 dB weaker than a first-adjacent FM signal, it becomes subject to adjacent spillover.

That’s why being in-between major markets always fascinated me.

I grew up in northeastern Ohio but my family would take frequent trips to New Jersey, where I live now.

The northeastern U.S. offers more opportunities for this phenomenon than most areas in the country, with the spacings of FM stations naturally tighter. The spacings are within what the FCC classifies as Zones I and I-A.

Central New Jersey is a prime example of this, driving up the New Jersey Turnpike near Exit 8A, for example, where the New York City and Philadelphia Class B FMs are about equidistant.

Most New York City and Philadelphia FMs follow the same 8 MHz separation pattern. 101.9 WFAN(FM), for example, is 2 MHz below 102.1 WIOQ(FM). Back in the day, I always tried to seek out the signal of 101.9 WQCD, when it was smooth jazz.

In portions of Mercer, Hunterdon and Middlesex counties, their signals can be just about equal in strength. That allowed even the poorer selectivity of some of my early portables to hear both stations.

This phenomenon was part of the motivation for my work on the RadioLand app.

Via the Longley-Rice method, you can find locations such as Plainsboro, N.J., where both New York City and Philadelphia FMs register with about a 60 dBuV/m predicted signal field strength.

The advent of HD Radio in the early 2000s added a bit of a wrench as far as being able to pull in adjacent FM signals with the IBOC technology. But the same signal differential typically holds true as far as 6 dB is concerned, with adjustment necessary due to recent power increases.

Other locations

The proximity between New York and Philadelphia, both top 10 Nielsen radio markets, makes their dial layouts unique.

There’s a few other examples. Philadelphia and Baltimore work with a similar setup, for example.

The Midwest, which is in the same zone as the Northeast, includes the areas between Chicago and Milwaukee along Lake Michigan. 96.3 WBBM(FM) sits next to 96.5 WKLH(FM), for example, producing the same effect riding up Interstate 94.

There’s no direct route between the cities of Detroit and Cleveland, but on the Lake Erie Islands in Ohio, including on Kelleys Island, the distance from the FM offerings of the two cities is similar. 101.9 WDET(FM) is adjacent to 102.1 WDOK(FM), for example.

I’ve never experienced listening in the areas between Los Angeles and San Diego firsthand, but the effect in southern California must be similar, too.

Areas like Baltimore and Washington, D.C. and Buffalo and Toronto are close enough to each other where they are primarily separated by second or third adjacent spacings.

Of course, there are a few offbeat cases.

Short-spacing

The Northeast is chock-full of grandfathered, short-spaced FM setups.

The stations involved either accept any potential interference based on a prior agreement or have their allocations that date back to when they were operating at a lower transmitting power.

New Jersey is the third-smallest state. Yet, two Class B FMs are licensed there, in 94.5 WPST(FM), from Trenton (though its antenna is actually in Fairless Hills, Pa.) and 94.7 WXBK(FM), from Newark. Approximately 58 miles separate the two stations.

103.3 WPRB(FM), licensed to Princeton, and 103.5 WKTU(FM), licensed to Lake Success, N.Y., and transmitting from the Empire State Building, form another close-quarters setup.

There’s several same-channel examples, including 101.1 WCBS(FM) and 101.1 WBEB(FM).

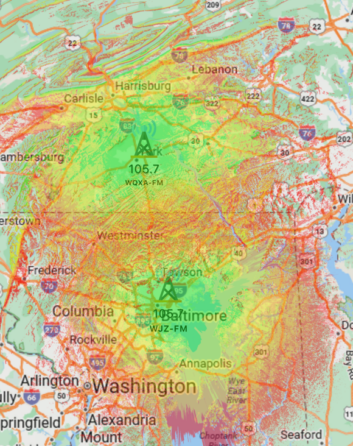

Perhaps the most notorious setup, though, is in the Beltway area.

105.7 WJZ(FM) from Catonsville, Md., and 105.9 WMAL(FM) from Woodbridge, Va., are two Class B FMs approximately 48 miles from each other.

The first time I experienced this, trying to hear 105.9 in its smooth jazz-formatted days while on a trip to the Annapolis area, I couldn’t understand why its signal was so impeded while other signals from the district were clear.

That’s not the only part of the short-spacing.

WJZ operates 47 miles from same-channel WQXA(FM) in York, Pa., also a Class B station.

A short drive on Interstate 83 separates the two areas.

With the aid of directional antennas, I have always been amazed at how the two signals have managed to coexist over the years.

Somehow they have.

If you have an example of locations where full-power signals collide, let me know!

Comment on this or any article. Email radioworld@futurenet.com.

The post When Markets Collide appeared first on Radio World.

(Some articles are truncated by the original site.)

Please visit the Original Source